Just a few years before the turn of the century (1998), American woodworkers began to be obsessed with weight. A picture appeared in “The Workbench Book” by Scott Landis. The picture showed Rob Tarule, planing away on a reproduction of a “Roubo Bench”. It was weighty and nicely joined – the race was on.

Since then, weight has been the watchword. But, alas, as with so many things in life, we may have allowed ourselves to be mislead. And, I’ll say it now, me too. Three hundred, fifty pounds sounded like a good weight. We appear to have identified weight with stability. And, believe me, brothers and sisters, they’re not the same thing!

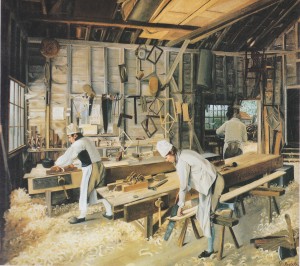

When one looks at the illustrations in “L’art du Menuisier”, it becomes obvious that these were to provide information about how the work was accomplished in Monsieur Roubo’s atelier. Note that there are no dimensions on the benches. The drawings are crudely isometric. And, after looking at the illustration of a half dozen or so benches “fanned out” in the shop, one can only assume that any one of them must have weighed a thousand pounds (1000 lbs.), or so. Also, there seems to be some notion that the method used to join the legs to the bench top is somehow superior. Consider this, timber frames need bracing against wind load. I’ve got to believe that those legs loosened up after a period of time (nail on the crossbracing!). I’m here to tell you that even in professional shops, things get moved around according to the work being done. What professional woodworkers have always been concerned with is stability. Stability and portability. Stability, portability and cost.

Not everyone has the space for a 1/2 ton workbench. Many amateurs and professionals alike work in shops that are rented space, or spaces (basements, attics, corn cribs, etc.) that would make it difficult to position one of these Leviathans.

If one looks back at historic documents (carvings, paintings, drawings) other than Roubo and Deiderot, a different picture begins to appear. Consider the English joiner’s bench. They are now commonly referred to Nicholson benches. But the design was around long before Mr. Nicholson arrived on the scene. He merely documented what was normal in English shops of the day. Some of these benches reached staggering proportions, as the ones used early in the twentieth century for the assembly of wooden air frames.

Scandinavian and German style cabinetmakers benches have long been the standard of both European and American shops. By comparison to anything in the “Roubo” class, they appear puny. But they became the standard for one reason, they fit the needs of the work to be accomplished.

Recently I read a post by Tomas Karlsson at www.hyvelbenk.wordpress.com on a very nice portable workbench with some very interesting features. In case you’re not a follower of the “goings on” at Høvelbenk, you should be. In case you don’t already know, Høvelbenk translates to planing bench. The guys at Høvelbenk investigate all aspects of benches designed for woodworking. IMHO, it is a “must read” blog, along with its “sister” blog, www.skottbenk.wordpress.com.

Another “revival” seems to be in the making. And it’s good news for anyone who is interested in a stable, reasonably portable, professional workbench. Enter the “Moravian”. The design has been around for several hundred years. Easily built, movable and stable, very stable due in large part to the legs be splayed (as opposed to raked). Høvelbenk has a nice post on a Moravian bench built by one of Tomas Karlsson’s students, Anton Nilsson.

Roy Underhill has been offering a class in Moravian Workbench construction, lead by Will Myers at the Woodwrights School.

Before I forget, Jeff Branch has put up some pretty nice drawings of a Moravian bench he plans to build. You can see them at www.jeffbranch.wordpress.com.

I said I’d never build another workbench. But I’ve eaten my words before and when served with some appropriate beverage, they’re not half bad. I think that I would add a center stretcher between the two upper trestle rails. It seems to me that the locator pins holding the top might take some unnecessary but avoidable stresses. I’d probably lag bolt the top. But that’s just me and I’m not going out to jobsites anymore (I’ve become a “woodworker of leisure”, in any number of ways). I think I’d opt for a couple of antique cast iron vises (Oh! My goodness, I think I’ve got a couple of those stashed away, if I can just find them.)

So. If it’s an altar you’re wanting, by all means, go buy yourself a stake truck full of heavy timber and build yourself a Roubo. But if you’re desirous of a stable, portable platform upon which to carry out the manufacture of various assorted parts associated with woodworking projects, think “Moravian.”

And by the way, if you can move this bench around while planing, you probably need to sharpen your irons. There just isn’t enough weight to compensate for dullness.